Would you like to learn more about the Eidsfoss’ history, as you enjoy beautiful and scenic surroundings? Then you should consider a walk along the cultural path. The long route is approx. 2 km on small gravel roads and forrest paths, while the shorter one is 1,2 km. The path takes you through the centuries, from the period prior to the ironworks was established in 1697, to the last stoves were produced in the 1960s and right up until today’s Eidsfoss. Enjoy!

1. “City” Centre

Bråtagata (The Garden street) is were the first workers homes were built during the first period in the 1700s. At first the buildings were one story high but as the number of workers and the families’ grew, a second floor was added (1900 – 1912). The name reflects that each appartement had a patch of land, were they could grow their own vegetables and maybe keep a pig or some chickens. In Bråtagata 49 a post office museum resides today, and you will find the exhibition “Til Elise” in the tavern. This exhibition tells the story of the destiny of a worker’s wife that was widowed in the early 1900s.

2. Hauane (The Heaps)

Until it became municipal in 1875, the school was run by the company. The first school came as early as the mid-1700s, when all ironworks were imposed to hold a paid teacher and a school building if it sustained more than 30 children. After the school was moved, a library resided in the buidling and today the municipal museum and the county hold offices here. There is also a school museum and an exibition about one of Norway’s first female ministers of Parliament, Rakel Seweriin.

Hauane is one of three working-class quarters at Eidsfoss, with buidlings dating back to the 18th century. The brown building across the old School was a guesthouse called Pynten (the Decoration). It was where the charcoal manger rated the quality and price of the charcoal farmers delivered to the ironworks. The whitewashed villa downstream from the school house, is a reconstruction of “Bekken” (the Stream). It was the Olsen Thon-familiy’s residence. Olsen Thon owned the company together with the Schwartz-Family in the early 1900. Please respect that all these buildings, except the school house, are privately owned.

3. The Industrial Area

The blast furnace, the heart of the ironworks, was approximately where the central parking lot is today. It was the most important production building, as it was where the pig iron was produced, and was among the first to be erected after the ironworks was established in 1697. However, the production of pig iron was phased out in the 1800s and the company became an iron foundry, utilizing cupola furnace to remelt iron scrap. After the foundry shut down in 1961, a factory producing metal textiles for the paper industry, was established in it’s buildings. Today, the company Mar-Kem hold the industrial past alive. They mainly produce stainless steel products for off shore production og oil and gas.

As the company transitioned into an iron foundry, steam and later electric power replaced direct waterpower. When the river lost it’s importance as an energy source, the industrial buildings were moved downstream, where they still are.

4. The Bath, the Power Station and the Assembly House

Here are several interesting buildings from the early 20th century. The wooden building on the right is Eidsfos Hall. The industry’s workforce erected the building in 1909, and it was funded by the owner’s wife Thrine Schwartz, born Anker. She contributed with 2000 kroner, but some terms came with the money. The assembly house was to be a place for enlightenment and education of the workers, while political agitation was banned. An increasingly politically aware working class soon found themselves in need of a new assembly house, and Varden (the Beacon) in Orevika, a few hundred yards west of Eidsfoss, was built in 1931.

The workshops and the owners’ houses (and Eidsfos Hall from 1909), had electricity since 1895, but the dynamo house in the old mill burned down in 1914. The new power plant saw completion in 1915, and during the 1920s, even workers homes got electricity. The brick stone house beside was built as a public bathhouse in 1908. In sum, these efforts raised living conditions for Eidsfoss’ citizens, and can be seen as an expression of the social-liberal notion that bettering conditions for workers would inhibit the growth of socialism.

The area is used for festivals, markets and concerts today, and popular events like the Eidsfoss music festival, the Stone gathering and the children festival Lyckliga Gatan (“Happy Street”) takes place here each year.

5. The Manor and its Garden

When Eidsfoss ironworks was established in 1697, there was already a two-story farmhouse here, called «Eid». The first owner, Caspar Herman Hausmann, refurbished the buildings according to his high rank and position, and used them as offices and housing for the administration. His son Fredrik Ferdinand Hausmann constructed around 1750, a brand new one-story, symmetrical building with nine rooms, situated on the same site as the former house. The second floor with the characteristic roofing was added in the 1770s. The gardens and allées are probably from the early 1800s.

Other preeminent owners of Eidsfoss’ ironworks have been Drammen-merchant Peder von Cappelen and his wife Marie Christine, who purchased Eidsfoss ironworks in 1795, and the Schwartz family, who bought the company in 1873. The main building remained the latter family’s home until 1987. Eidsfos Manor house has been a preserved cultural heritage since 1923, and in 1990 a foundation was formed, to preserve and develop the buildings and surrounding gardens. Today, the main building contains a restaurant and banqueting facility.

6. The Church

The ironworkers originally belonged to the parish church in Hof, 7 km from Eidsfoss. When the local church council rejected the ironwork’s application to hold ceremonies at the newly built schoolhouse in 1893, the workers wished to erect a chapel in Eidsfoss. It was realized through a “church tax” payed by the employees with contributions from the two owners Schwartz and Olsen Thon. Unfortunately, on November 30th, 1903, the nearly finished chapel burned to the ground. It was quickly rebuilt, and on July 20th, 1904, bishop Bang could finally hold his inauguration speech in Eidsfoss Chapel.

The cruciform church is erected in studwork with standing panel. The interior represents a Nave church with a narrow cross containing sacristies and galleries. The artist behind the altarpiece is Elna Schwartz Särstrøm, daughter of the ironworks owner. Architect is H. Sinding-Larsen and builder is A. Kolstad. In 1958 A/S Eidsfos Verk gave the church to Hof municipality. The local church council has owned Eidsfoss church since 1997.

7. Kølabånn

This place is called Kølabånn, probably because charcoal was produced here. Huge amounts of charcoal went into the preparation and production of pig iron in the blast furnace and other processes at the ironworks. Farmers from within a particular radius, the circumference, were ordered to produce and deliver a specific amount of charcoal. While this spurred some complaining, it also represented a welcome income for the 300 farms in question.

The steam ship Stadshauptmand Schwartz was trafficking the lake Eikern between 1903 and 1926. It was named after Johan Jørgen Schwartz, father of the ironworks owner and mayor In Drammen. It was part of a fashionable roundtrip between Kristiania (Oslo) and Tunsberg. The company got financial problems during the economic downturn of the 1920s, and after being out of service for several years, the ship sank while moored in 1931. Attempts to raise her in 1933 and 1972 failed, but in 1995, a group of locals finally succeeded. Today she is displayed as a “Floating Cultural Heritage on dry Land”.

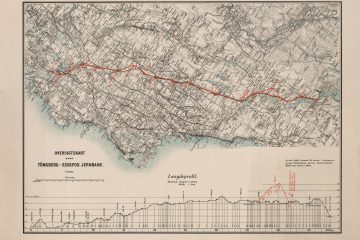

8. Waterfalls in River Eid

There is a 17-meter drop between the lakes Bergsvannet (to the east) and Eikern (to the west), which has been utilized for watermills since the middle ages, and sawmills since the 16th century. A dam was built when the ironworks was established in 1697, and the water led into a system of channels and sluices that drove the paddlewheels that gave life to hammers and bellows in the huts and workshops. The blast furnace also depended on waterpower.

The dam was originally built in wood. As the lake rose, farmers complained over loss of fertile land, and in the 1720s, Eidsfos Verk negotiated a “friendly settlement”. The settlement ensured farmers a yearly compensation – an arrangements that still applies today. A new cement dam was built in the early 20th century.

You can still see big square stones on the south river bank by the Bettum workshop. This is what remains of the hammer hut. Together with the blast furnace, it was the ironworks most important production building. Further downstream, other ruins and traces of buildings from the ironworks period are still visible. Read more about the attractions along the Cultural path.

The Cultural path was established in the early 1990s and is currently being upgraded. 18 Historical signs tells the ironworks history along the 3 km long path.

Welcome to a time travel on foot!