Power from the 17 meter waterfall between the lakes Bergsvannet and Eikern, had economic impact long before the age of the ironworks. Already in the 14th Century, there were established three mills along the short river-stretch “Eid”.

The water powered vertical sawmill arrived in Norway in mid-16th Century. They were mainly owned by the city bourgeoisie, who held privileges to the timber trade. There were two such sawmills at Eidsfoss in 1545, owned by a Dean in Tunsberg, three at the most. When the ironworks was established, the rights to the mills and sawmills were taken over by the company. In 1845 the ironworks established a modern circular sawmill where the river expires in lake Eikern.

The establishment of an ironworks

Several ironworks were established in Norway in the 17th and 18th century. As Denmark-Norway was fighting Sweden for Nordic supremacy, it became increasingly important to strive for independency from Swedish iron. Iron was the main strategic material of its age, as both weapons and ammunition was made from it .

The ironworks had their first golden age ahead of and during “the Great Nordic War”, that broke out in 1700 and lasted 21 years. The decades predating the Napoleonic wars were also good for business. The tight connection between iron and war is illustrated by the fact that the alchymist used the same symbol for denoting iron, maskulinity and Mars, the greek god of war. Vast water power potential, forests and iron ore deposits were conditons that made Norway suitable for the Danish-Norwegian state’ s venture.

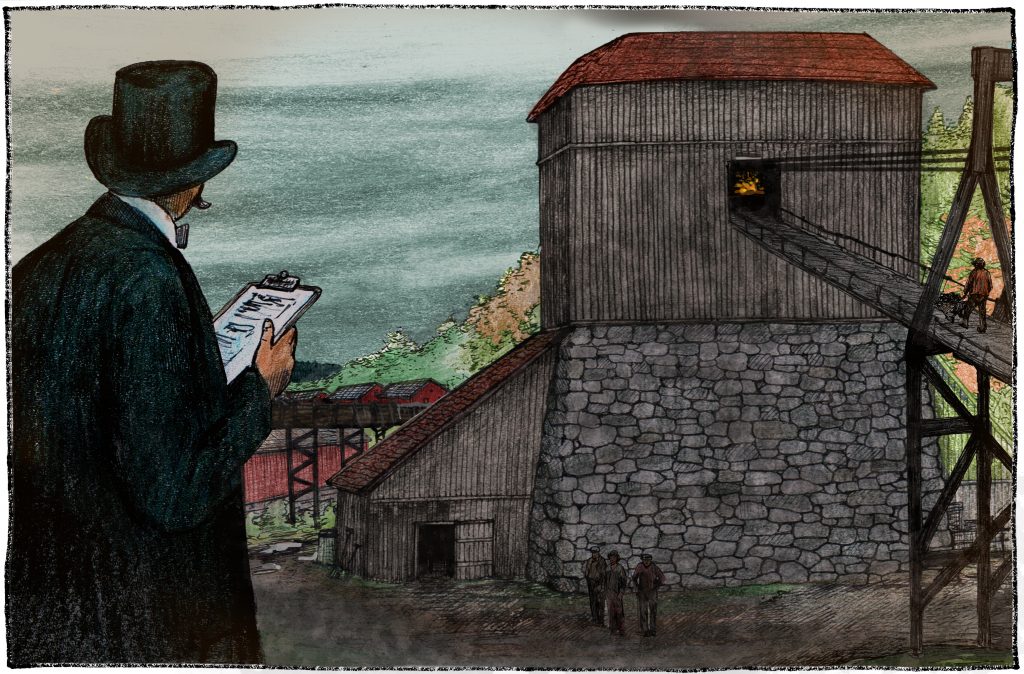

The Blast Furnace

The blast furnace was the heart of the ironworks, because it was here that the pig iron was produced. Melting iron ore requires a temperature of 1540 degrees Celsius, and the blast furnace was equipped with water-powered bellows to ensure such high temperatures. The ore was first roasted and beaten into smaller pieces and layers of ore and charcoal were placed in the blast furnace. Lime was added if necessary. The blast furnace master used all his senses to determine whether the blend and temperature were right, and an experienced and knowledgeable master was the key to success. Pig iron gathered at the bottom of the furnace, while cinder floated up on top. Pig iron was drained out on the floor of the smelting hut, where it was casted into blocks or open or closed molds. The blast furnace was operating continously for 2-3 years at the time.

Know-how and technology came from Germany and was transferred orally. It wasn’t until the Royal Mining Academy at Kongsberg was established in 1757 (one of Norway’s first institutions of higher education), that expertize on subjects like metallurgy and mining developed. During the 19th century, the Norwegian iron industry struggled with low demand and increased foreign competition. Here at Eidsfoss, the blast furnace production was phased out in the 1880s, when the company, as most Norwegian ironworks, became an iron foundry. That meant remelteing scrap iron in cupola furnaces. The last iron stoves were made at Eidsfoss in 1961.

When the world came to Eidsfoss

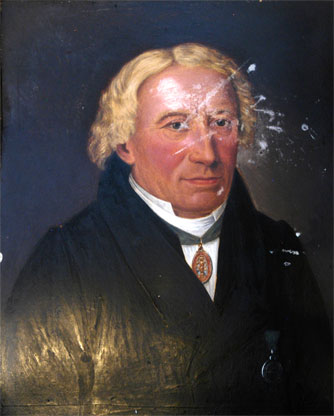

Eidsfoss ironworks was established on the kings initiative. He gave the honorable assignment to lieutenant general Caspar Herman Hausmann (1653–1718) in 1697. The successful timber merchant came from the german dutchy of Holstein. The dutchy was in a personal union with Denmark-Norway at the time. Hausmann was half brother to Ulrik Fredrik Gyldenløve, Governor of Norway, Count of Larvik and proprietor of Fritzøe ironworks.

The first issue in which Hausmann attended, was to secure a deal with Count Wedel-Jarlsberg, in order to take over the right to exploit the natural resources and order nearby farmers to perform work duties, such as the transportation of iron ore and charcoal. It took one year to get the deal in order, but soon Eidsfoss grew to be an active industrial site. A stove plate from 1698 shows 9 different buildings and during the 1700s both the three workers areas Hauane, Bråtagata and Gata and Eidsfos Manor emerged. After Caspar Hermans death in 1718, his wife Karen Toller ran the ironworks until she died in 1742. Their son Fredrik Ferdinand ran it until 1753, when Hagemann, who also built the stately manor house Gausen in Holmestrand, took over. After Hagemann there were several owners, among them Batholomæus Rasch and the Deichmann-brothers, until the Cappelen-Family aquisitioned Eidsfoss ironworks in 1795.

Charcoal and Conflicts

Norwegian ironworks privileges consisted of several special rights. The ironworks were for example exempt from paying a 10 percent tax called “tiende” (“a tenth”) as well as enlisting soldiers for war duty. Within the circumference (a radius of approx 2.5 miles) ironworks owners could exploit natural resources and order farmers to produce and transport charcoal and iron ore. The farmers in Vestfold were freeholders and enjoyed a somewhat better economy than most farmers at the time. They complained that the pay didn’t reflect the fact that the transportation took a great toll on men and horses. They also complained about how they were treated when delivering charcoal at the ironworks. The farmers had a powerful ally in the Count’s manager, and the struggle between him and Hausmann went on for years. The outcome was that the farmers within the Eidsfoss circumference achieved better conditions than what was the case at most other ironworks. Over time, producing and transporting charcoal nevertheless became an important income for many of the local small-time farmers.

Peder and Marie von Cappelen

Drammen resident, timber merchant and grocer Peder von Cappelen acquired Eidsfoss ironworks in 1795 and ran it until his death in 1837. He simultaneously ran other ironworks and sawmills, in addition to his extensive trade activity. The Cappelen period was a good period for Eidsfoss ironworks. He procured a modern blast furnace and built better roads, and when he bought Kongsberg ironworks in 1824, Eidsfoss became part of a modern industrial value chain that consisted of mines, ironworks and fabrication, as well as woodlands and sawmills. This created virtous cycles for Eidsfoss, who overcame the economic depression that followed the Napoleonic wars better than most Norwegian ironworks.

Peder was married to Christine Marie, and the couple lived with their two daughters at Eidsfos Manor. After her husband died in 1837, Madame Cappelen moved to the city Christianfeld in Denmark, in order to join the Herrnhut Brethren Church, the pietist direction that she and her husband both had sworn allegiance to. The Brethrens had built Christianfeld as a model town, and from here Christine Marie ran the ironworks in companionship with her daughters and sons i law. Christine Marie Cappelen is also reckoned to be Norways first female botanist, and she collected and registered plants that were common to Eidsfoss. It resulted in the hand written flora; Wild growing Plants at Eidsfoss and the Surroundings, which is the first scientific work conducted by a woman in Norway. It created school for later floras and can be found at the botanical museum in Oslo today.

The Tunsberg-Eidsfoss Railway offered new opportunities

In the 1870s, Eidsfoss transitioned from an ironworks to an iron foundry, and in 1884 the blast furnace was cleaned out for the last time. As a foundry, Eidsfoss remelted scrap metal in a so-called Cupola furnace instead of producing pig iron from ore in a blast furnace. The company ventured in agricultural machines, casted products such as mullions, picket fences and garden furniture, all popular articles in bourgeois homes, in addition to their popular woodstove models. The railways freight wagons were also produced at Eidsfoss, and the company continued to make railway cars at Sundland in Drammen until 1968. Seven years before, all iron production at Eidsfoss had stopped. A factory that produced metal fabric for the paper industry was established in the old foundry however, and it existed until 1988. Today it is Mar-kem, a company that produces steel tubes for off-shore businesses, that holds Eidsfoss’ industrial traditions alive.

Days of demolition and the rise of a new community

As the iron industry closed down, workers moved away from Eidsfoss. In the mid-1970s, the workers houses were hence clearly marked by decay. The company wanted to tear down some of the buildings in order to better traffic conditions, and the plans for a new road meant that most of Bråtagata had to be demolished. That spurred a local initiative that gained support from Heritage authorities and renowned artists, and a foundation was established in 1978, to ensure life and light to return to the old houses. Road safety was still secured, by putting up speed bumps (a new invention in the 1970s) and the introduction of a 30 km speed limit. In the late 1980s, a great deal of work was undertaken as part of an employment program. Unemployment was high in Norway at the time. The program facilitated for the cultural path and many of the historic buildings were refurbished. In the early 1990s, Eidsfos Manor and the ironworks museum were organized as foundations and the museum established their exhibition in cooperation with Vestfold county museum. The combination of cultural events and historical dissemination has continued to characterize the community since.

Are you interested in learning more? Take a walk along the cultural path, were 18 signs take you further into Eidsfoss’ history.

The water fall, forest and the possibility for transporting goods and products on nearby lakes, has been prerequisites for industrial development at Eidsfoss since the middle ages. It didn’t really take off before an ironworks was established in 1697. 300 years of technological and social developments followed, but decline took hold in the latter half of the 20th century. Today, culture has replaced industry as the community’s main activity.